Of Documentary Photography and God

This semester I took a course on Documentary Photography in Yale-NUS taught by Tom White, which culminated in a mini-exhibition of the class’ projects last weekend.

At the start of the course, I shared that the documentary style is used to record significant historical and present-day evidence of events and to reveal important pieces of information relevant to the event. It really is a style that is more art than science; it is the process of presenting a story, through a photographic medium that can be interpretative with a sum-of-parts approach to explain a ‘truth’ or a ‘reality’.

The course revealed different perspectives of how documentary photographers portray their work. Here, I will highlight some notable figures in the field to bring across my views of the conventional use of the documentary style of photography, some of the radical styles documentary photographers have deployed in their work, and my personal take on documentary style as a whole.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank

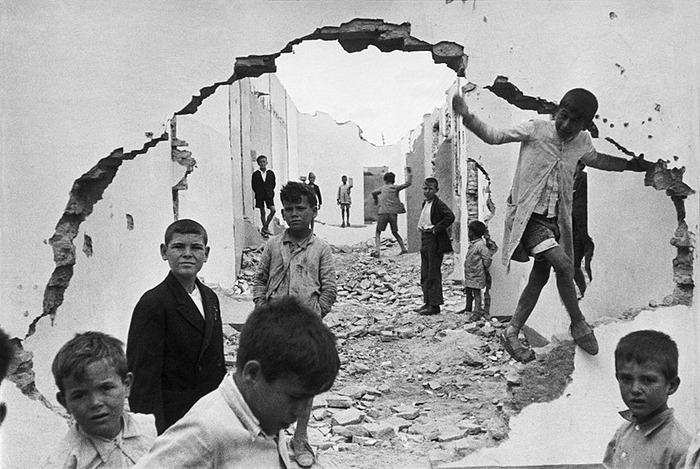

The first documentary photographer I came across before reading this course was Henri Cartier-Bresson and the use of his 35mm, candid-esque street photography, trapping moments in stills. Undoubtedly, the earlier days of documentary photographer was seemingly easier for the common man to comprehend at face value.

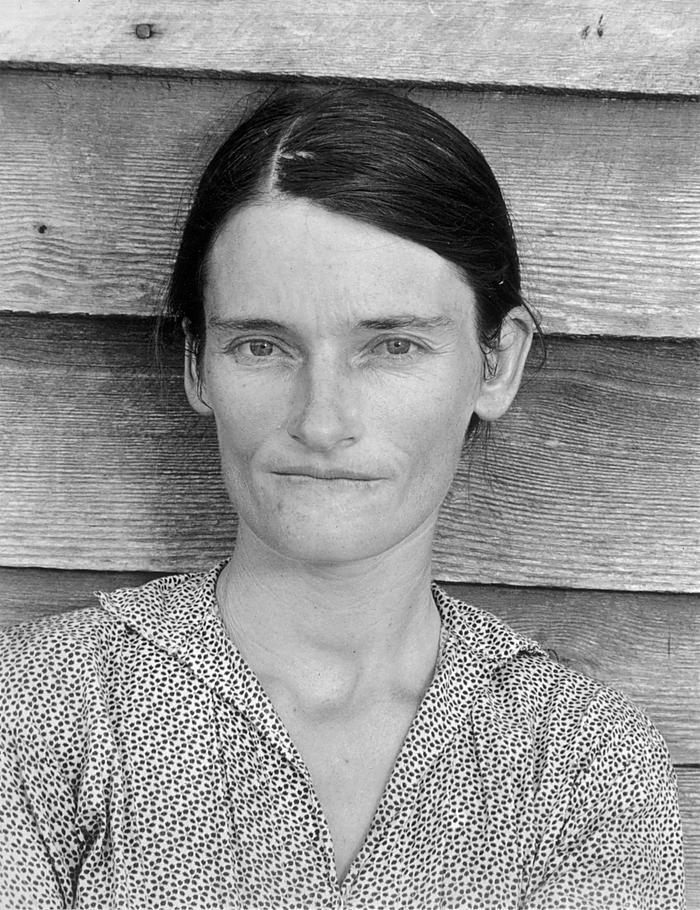

As times changed, the style of documentary photography also gradually evolved. Specific in the course, we spoke of Walker Evans and James Agee and the marriage of three photo series — one of which entitled Now Let Us Praise Famous Men. The series, Three Tenant Families, was produced together with Agee’s strikingly descriptive text accompaniment with a primary focus on the ordinary, in Evans’ photographs.

Photographers tend to adapt the style of their predecessors, as with Robert Frank and Walker Evans. When Robert Frank put in his application for the Guggenheim Fellowship 1954, he stated that it was a project that would “shape itself as it proceeds, and is essentially elastic”. However, this course unveiled that documentary photographers conjure up an overarching theme prior to commencing a project — Frank seemed to have done the same. Despite taking 27,000 photographs with only 83 photographs published in The Americans, Frank photographed the people’s experience as-is — not by “looking at it but [by] feeling something from it”.

Because of the number of photographs he took, it made selection and elimination, and sequencing incredibly difficult. The 83-photo series however, needed no captions or textual accompaniment aside from the date, time, and location of the photo taken because of the narrative he sought to portray in the series, which was immensely satisfying to flip through and to thoroughly understand post-1950 America through Frank’s eyes.

“Frank not only described the sombre places and black events, but also these people, places, things that seemed true and genuine, with a spiritual integrity or a moral order.”

— Sarah Greenough on The Americans

Conveyor to the Ceiling by Daniel Donnelly

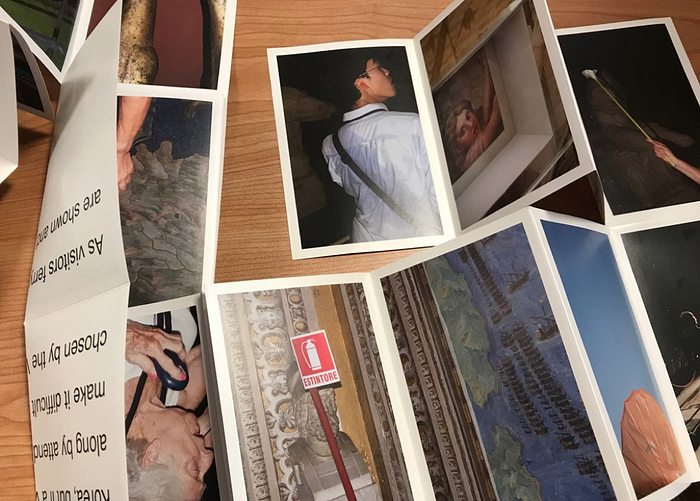

Daniel Donnelly stepped into the class as one of the guest speakers to share his experience on his work, Conveyor to the Ceiling. The series came in a foldable map with photographs printed on the one side, and a prose on the other — captions that fit the photographs and a narrative that can be read in full when unfolded entirely. It was an interesting presentation method to portray how visitors and tourists to the Sistine Chapel photographed everything and anything along the way to the pièce de résistance, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, where (ironically) no photo-taking was allowed. Donnelly brought across the message of how tourists at times miss the point of visiting such places of interest.

With the Conveyor to the Ceiling, one can easily see how people generally undermine the entire journey they take to the actual area of interest (i.e. ceiling of the Sistine Chapel). Considering how this is an atypical way of documentary photography, a form of “monitoring” human behavior, if you will, it still depicts how humans may be fickle and come with the pre-conceived notion of seeing only the ceiling instead of taking in entirely what the Chapel offers.

“Behold: the IKEA-esque route in the Sistine Chapel where people would take photographs of all the things they did not come for, but are not allowed to take photographs of the one thing they did come for.”

— Daniel Donnelly

The Provoke Style: Taki, Nakahira, Okada, Takanashi, and Moriyama

One class that particularly stood out was how some photographers had very radical ways of employing the documentary style: Provoke photographers deliberately mishandled their cameras to create a shaky and blurry result which has since morphed into a new style of documentary altogether. Provoke photographers constantly challenge the status quo of how conventional photographs are taken, and produced a series in the context of social upheaval. While Frank deployed a style of photography answering the questions of “What should we photograph?” or “How should we photograph?” Provoke photographers were asking questions which were more fundamental: “What is photography?”, “Who becomes a photographer?”, and “What is seeing?”.

Through this process, I was better able to appreciate why and how the Provoke style came about and immediately piqued my interest when it came to working on my project, The Distance from God.

In the Making of The Distance from God

In my project, I wanted to fuse the Provoke style of photography with Frank’s methodical way of capturing stills, selecting and eliminating, and then sequencing these photos to tell a narrative. I was initially working on the theme of religious hypocrisy; on why the seemingly religious still commit vices despite being Catholic. Over the semester however, the photos I have documented revealed a more crucial narrative I knew I had to portray through in the final series: the idea that it is one who defines what religion is, instead of the conventional wisdom of how religion shapes one’s beliefs and values.

This process involved taking over 240 photos, then selecting and eliminating photos to 120 photos (first-cut), and subsequently to roughly 50 photos (second-cut) that were suitable to tell this particular narrative. The Distance from God resulted in a 26-photo series (~10% conversion rate), quipped with bible verses as a form of caption to fit the pocket-sized prints (roughly A7 sized), in a black leather-bound notebook that resembles a bible. I sought to illustrate a false sense of security, uncertainty, and transience, even with the presence of God in this series of photos. I had hoped to juxtapose the very real scenes documented, with what is considered divine.

Photos in the series are mostly in monochrome, with the exception of four photos, which I felt was necessary to better bring across the essence of certain elements — such as the lighting on a neon sign, the essence of life in technicolour and transience through the spinning wheel, and the natural light that comes through at the back of the church’s iridescent-painted glass-wall. It was important to depict certain points of confusion in the series (cleverly, I hope) sequenced between photos of clarity and stillness, which was the justification behind my style choice of both Provoke and Frank respectively.

Embed in the series are subtle nuances I hope viewers can also appreciate — the use of light and sunburst, symbols that resembled Jesus’ cross, and most importantly the feeling of standing in a Catholic’s shoes, pensive about questions on religion and God. Finally, Catholics often speak of being closer to God, which is precisely why the series was (aptly) titled as such. See Excerpt below.

Concluding Thoughts

This course has undoubtedly opened my eyes to how photography can be like, and the boundless possibilities given a suitable overarching theme. From the selection process from the volume of photographs, to sequencing, editing, and the classic modernistic style vis-à-vis an alternative, more radical approach of documentary photography, all are applicable in different ways and in different contexts. Portraying reality using photography as a medium can be a rather contentious topic matter especially with various editing software today. With the course learnings however, one can take away certain aspects to document genuine moments using styles which are appropriate; and that can either just push a message across, or bring about revolution.

If you’d like to take a look at my work on The Distance from God, feel free to drop me a line; hold onto the applause button for as long as the “Our Father” prayer holds.

Excerpt of The Distance from God

“There is but one God, and religion is still an exceptionally tricky discussion matter today — who believes what and why. But as humans, whether or not we believe, we are subjected to the world’s perception of us. At some point in time we find ourselves keeping our chin above the water whilst others surf on by. What makes them different from the rest of us? Is it the weekly attendance in the house of God that defines one’s passage to the Garden of Eden? Does it truly matter if they pray more fervently than we do? Could there be more to life than faith and belief? What defines the very space between God and man? How do we measure this distance, or even hope to scale it?

This series centres around my personal journey in exploring the different facets of looking at something divine in a very strikingly real way, to answer just a few of the questions on The Distance from God.”